On February 17, 2004 the state of Texas executed Cameron

Todd Willingham for the arson murder of his three children in 1991. By that time the scientific evidence upon

which Willingham had been convicted had been challenged by experts in fire

science, the case had become something of a cause célèbre for anti-death

penalty advocates, and perhaps most importantly it was a political football of

epic proportions. All his appeals denied,

clemency, and even a 30 day stay to investigate the scientific challenges

denied by hard line law and order Governor Rick Perry, Willingham ate his last

meal and was executed by lethal injection.

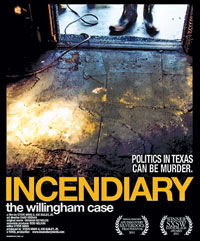

Incendiary, the award winning documentary

directed by Steve Mims and Joe Bailey, Jr., is the disturbing account of the Willingham

case and its aftermath. Although the

film comes to no absolute conclusion about the man's guilt or innocence, it

makes clear that the evidence upon which he was convicted was flawed—a

combination of junk science and unreliable witness testimony. Moreover the legal representation he was

afforded by the state was something less than stellar. Though the film does leave the question of

guilt open, it seems clear where the film maker's sympathies lie. At the very least in refusing to take an

objective look at the new scientific evidence the powers that be in the state

of Texas failed to give the accused a fair hearing, at worst they executed an

innocent man.

The film maker's interest in the case, as they explain in an

interview included as a bonus on the newly released DVD, stemmed from a 2009

article in The New Yorker by David Grann, in which he

vividly takes the reader from the house fire to the execution, and introduces

all of the key players. Recognizing a

good story, Mims and Bailey began their own investigation. They managed extensive interviews with those

who questioned as well as those who supported the arson allegations so that

they were able to create a complementary visual account of the history of the

case to that of Grann. Then when the

Texas Forensic Science Commission began to look into the case after the

adoption of new standards for fire investigations by the National Fire

Protection Association they were able to follow the new attempts to clear

Willingham's name. It is a story that

plays like a TV forensic drama.

It has a cast of characters made for TV. Willingham, himself, as nearly everyone

interviewed acknowledges was far from a nice guy. Indeed, he comes off much better in Grann's

article than he does in the film. Elizabeth

Gilbert, a volunteer with an anti-death penalty group, who befriended him in

prison, gets much more time from Grann than she does in the film. She is interviewed but not as extensively as

the two major fire scientists, more than likely because she comes across rather

blandly on screen, whereas the two scientists, Lentini and Hurst, are attention

getters.

The film begins with Lentini ridiculing the original

forensic investigation. He is assertive

and acerbic. He comes across as a

straight talker with no tolerance for fools.

Hurst, on the other hand, has the appearance of a street person—a long

unkempt grey beard, stooped and thin, he looks in need of a good meal. Yet when he speaks, he speaks with authority,

and it turns out he has the credentials to back up what he says. He explains the science with the kind of

clarity that makes it intelligible even to scientific illiterates.

The other side has its dynamos too. David Martin, Willingham's defense attorney

is adamant both about the quality of the case he made for the man as well as

his belief in his guilt. He teasingly

allows that were it not for attorney client privilege, he has enough damning

information to prove Willingham's guilt.

Then there is John Bradley, the district attorney appointed by Governor

Perry to chair the Forensic Science Committee, who seems to be doing his best

to stall the hearings. Although he is

never interviewed for the film, his contretemps with Barry Scheck lawyer for

the Innocence Project makes for some real life dramatic conflict. Later reporting seems to indicate that

Bradley is changing his opinions about reconsidering scientific evidence as a

result of another case.

It is hard to come away from this film feeling that justice

has been served in the Willingham case.

It is almost cliché to say that the death penalty once carried out

doesn't give you the opportunity to correct mistakes. You have to get it right. There are those that believe that the

evidence that convicted Cameron Todd Willingham was flawed; there are those

that believe that flawed or not he was a guilty "monster." Justice would seem to indicate that new

exculpatory evidence should at least be considered and evaluated. This is the message of the film. It is an important message, powerfully delivered.

No comments:

Post a Comment