This article was first published at

BlogcriticsWhat disturbs me most about Mordecai Richler's 1997 novel,

Barney's Version, now available in a new paperback edition as well as a major motion picture with Paul Giamatti, is that it took me almost fifteen years to get around to reading it. This is one hell of a masterful piece of fiction. It has everything you could want from a novel—humor and poignancy, complexity and passion, eloquence and a specific aesthetic point of view.

Barney's Version is not only a great read, although it is that;

Barney's Version is a work of art.

Now in his sixties and having trouble remembering the names of the Seven Dwarfs, Barney Panofsky sits down to tell the story of his life, ostensibly to defend himself against what he sees as a scurrilous attack in a book by a writer he once thought of as something of a friend back when they were young expatriates living imitation Bohemian lives in Paris. Barney, in spite of the fact that he tells his own story, doesn’t come across as a particularly nice fellow. He is loud and can behave obnoxiously, especially when dealing with poseurs and those he considers pompous. He is defensive about his roots, his religion and his feeling that he has sold out to the money grubbers, and his defensiveness more often than not takes the form of aggression.

Three marriages: his first wife dies and she is followed by two divorces—although he still carries the torch for his last wife. He has made a fortune producing schlock television shows for broadcast in Canada. Not particularly religious himself, is tuned in to both the anti-Semitism he felt as a child in Montreal and still feels as he writes and his distaste for the pretentions of many of the Jews around him. He is an aggressive type-A personality who goes after what he wants without regard for the feelings of others. He is not afraid to flaunt his wealth and use his position to get what he wants, and if he needs to finagle a little, bend a law here and there, he is not above it. He can be foul mouthed and sarcastic when he likes you and a vindictive son of a bitch when he doesn't. Yet despite all this, he is a vibrant exciting character filled with a will to live life to the fullest.

Back in the 19th century when Robert Browning was writing poems in the voices of a gallery of rather disreputable characters, he pointed out that what he was trying to do was present them in such a way that they would make the best possible case for themselves—what he called the defense of the indefensible. In some cases they were outright villains, in others, charismatic reprobates. But however a reader felt about them, that reader's feelings came directly from what they had to say about themselves. Richler is doing the same thing. Like Barney, or hate him: it is from his own mouth that you must make the determination.

He is a curmudgeon, but he is not one of those loveable curmudgeons with a heart of gold hidden under the bristles. He can be cruel. He is self-centered and selfish. He is perfectly willing to use people. And still you can't help liking him, possibly because of his voice. He tells his story with what seems like unvarnished honesty. He doesn't seem to be hiding anything. When he denies having done something especially egregious, the fact that he has been owning up to all these other misbehaviors gives some credence to his denials.

Moreover the story just seems to pour out of him. It reeks with sincerity. It never seems artificially pointed to make a case for the reader, despite the fact that it obviously is. It is filled with digressions, memory lapses and angry rants on all sorts of subjects from Francophile politics and the state of contemporary hockey to literary pretentiousness and political correctness. At one point he compares what he is doing to books like Sterne's

Tristram Shandy ; if Sterne could get away with all the beating about the bush, why not Panofsky? There are even points where he suggests he may well be setting the spool of his life on rewind and "editing out embarrassments, reshooting them in my mind's eye." Not only does he ramble and digress he admits to the possibility of his own unreliability. He is a narrator with whom it is a pleasure to spend four hundred pages.

And if Barney is not to your taste, there is a supporting cast of the kind you might find in a Dickens novel. There are the three wives: Clara, an expatriate artiste with real emotional problems who becomes a feminist icon years after her death; the second Mrs. Panofsky (as she is always referred to in the novel), a Jewish Canadian Princess with a family pretending to be Wasps; and Miriam, the mother of his children, the love of his life and the woman he ultimately betrays. There is the Jewish fund raiser whose eyes light up when he hears about anti-Semitic acts because they foster contributions. There is Barney's hard drinking father, the only Jewish cop in Montreal. There is his best friend Boogie who may or may not be a great writer, but who is definitely a druggie and a procrastinator. And these are just a few by way of example.

There is something of a plot concerning what may have been a murder in Barney's past, but since it is only hinted at through most of the book, and revealed at the end, it would be horrendous for a reviewer to spoil any of it for the reader. Richler approaches it and backs away like child playing peek-a-boo. The details are less important than the game, and to know them in advance would spoil the game. Besides, the pleasures of this book are not in the plot; the pleasures are in getting to know someone like Barney Panofsky and listening to his version.

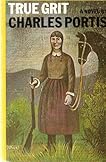

True Grit by Charles Portis

True Grit by Charles Portis